Cherokee Garage And Racing

Jerry Wimbish and Gober Sosebee with trophies on the hoods at the Cherokee Garage on West Peachtree Place, Atlanta. That's little John and Gene Hester on the fender and running board.

By 1942, the operation was in full swing.

“First thing I did was get two fellows who were with me at International Harvester. Grady Couch, Tiny Takguary and myself could produce one complete engine job a day for two hundred dollars, and that included flushing the radiator. Twenty-five bucks more and we added a new pressure plate and flywheel.”

Business was brisk. In 1949 things got even brisker. Gober Sosebee came by Billie’s place one day and needed a place to set up. Sosebee had been around the racing scene for a bout a decade and made quite a name for himself. For the next six years the name Gober Sosebee, the Wild Injun, Cherokee Garage and Billie Hester became synonymous in the racing circles. A ton of modified wins and their sparse venture into the NASCAR Grand National scene (Winston Cup) produced two wins and eleven top ten finishes in only sixty starts.

A couple of wins at Daytona’s old beach and road course stand out most in Cherokee’s racing history. One was a NASCAR modified race in 1950 and the other a sportsman division win in 1951. But the most excitement was another beach race they didn’t win but caused a rule change. Billie told us the story.

Gober Sosebee, Tiny Takguary, and Billie Hester are the first three, left too right, kneeling.

“We had just finished a pit stop and Gober came right back in for more fuel. Come to find out somehow a rag was stuffed down our old Army supply can and the gasoline was just trickling out. Jack (Smith) had fell out of the race early and saw the confusion. He jumped in the back of the car and told me to hand him the can and continued to pour while going town the track.” (Remember Billie use to rent a garage in Lathamtown from the Smiths).

So instead of a ‘splash and go’ it was a ‘Jack and go.’ Billie then said…”since the tank was designed to be fed from inside the car, there was no problem racing to the finish with Jack in the back.”

Except with NASCAR, who promptly dropped Sosebee several positions after the race.

“You couldn’t argue with Gober,” Billie laughed. “I always said his life’s ambition was to be stubborn and ornery.” NASCAR did not relent, but their rulebook was immediately rewritten…”no car shall carry more than one person at any time during a race, practice or warm-up.”

Gober Sosebee (50) and Jerry Wimbish (51) race at Atlanta's Lakewood Speedway in the fifties.

Billie said another time he arrived late for an event in Daytona, went to the track and saw what he thought was a convertible racing up the beach with a man’s head peering out of the side. Once the car got nearer he saw Gober trying to see where he was going. The car had earlier rolled several times and smashed the roof in, but ended up back on fours and still moving at a fair pace.

“Two of the three carburetors had been broken off at the manifold, but it was still going,” Billie said. “We rented a garage for $500 in town and repaired it, put in another windshield and straightened out the roof. Of course we were lucky to find a place with so many racecars in town and no where to work on ’em.”

Sosebee was famous for his trademarked power slides on the tracks. The late Jerry Wimbish, a teammate out of Cherokee stable who also worked a stock car driving school at the local Peach Bowl Speedway once said about Gober, “Sosebee got paid extra for all of that clowning because the crowds loved it. If he had drove the car different he would have won even more races. But he knew that.”

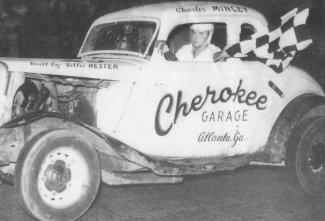

Another Cherokee Garage driver famous for his clowning was Charlie Mincey.

“But that was before he started racing,” Billie told us. “Bo Turner came by the shop one day and said that Roy Mincey’s boy was out there on Marietta Street doing ‘360’s on those double streetcar tracks. He said some day he’s going to rim one of ’em and not stop rolling until he reaches eternity.”

Ralph “Badeye” Shirley had Mincey making a few runs for him to North Georgia in 1950. Seeing how he loved to race the streets, he had Billie build him a racer.

“Ralph gave me a 1934 Ford and asked me to make Charlie a racecar around 1951,” Billie said. “We took it to the Peach Bowl and they’d let him start up front being a beginner. I still remember the likes of Roscoe Thompson and Jack Smith trying to turn him but the kid held his own.”

At the end of the season, Hester and Mincey were at the half-mile track in Jonesboro, GA (New Atlanta Speedway) and they both agreed the motor was cooked for the year.

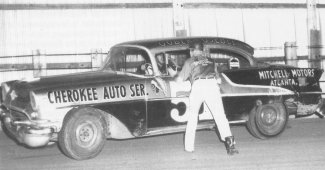

Charlie Mincey began his racing career in a Billie Hester prepared car furnished by Ralph Shirley.

“We hadn’t done nothing but changed the oil after the races that season, so we went ahead and put on some taller tires (700 C 16) and tied the shifter in second and let it peg out. Right when it crossed the finish line that engine scattered to pieces,” he laughed. Mincey himself continued on and went to many more victories, and engines, over the next thirty years.

By the later part of the fifties Hester was out of racing.

“Carl Kiekhaefer came in with all those Chryslers and told us he had seven million dollars in the bank, and we’d be running for second. Last car I was working on was a midget. I loved to watch them when they ran the Peach Bowl (in Atlanta). I had one taken apart with the frame and body in an out-building. Somebody broke in the shop and stole the engine, which I had disassembled in a 55-gallon drum. I don’t know but I assume they thought they were stealing some grease. Regardless, after that I just lost interest.”

Billie today finds racing a bit boring compared to his era.

“It’s all business now,” he said. “Once at Lakewood we’d burned some pistons on the car. There were two features that day; one modified and one sportsman. I told promoter John Caviness that if he’d run the modified first, I’d be ready for the sportsman. There was a motorcycle cop there by the name of Clark Quattlebaum. He put my mechanic on the back, pushed the siren and off he went up Pryor Road to my shop for parts. We couldn’t raise the engine out of the car, but we loosened it enough to move around the oil pan to install the pistons. This was no bush league race either. But you won’t see any of that going on today. We don’t get under the tree together. Racing like life has gotten fast and impersonal.”