Brandon Reed

By Brandon Reed

Posted in Columns 6/17/11

Following Sunday’s NASCAR Sprint Cup event at Pocono, Pennsylvania, the #18 M&M’s Toyota of Kyle Busch failed to pass post-race tech. According to reports, the Joe Gibbs owned Toyota was 1/16th of an inch outside the tolerances allowed by NASCAR.

The result was a $25,000 fine, the loss of six championship owner’s points and six championship driver’s points.

The debate over such fines and penalties has gone on for years. But today’s drivers should count themselves very, very lucky. Back in the “pioneer days”, drivers weren’t just slapped with fines. They were completely disqualified, or in some cases stripped completely of championship titles.

One of the drivers who seemed to get hit more than others was Georgia Racing Hall of Famer and two time NASCAR Sprint Cup champ Tim Flock. Tim’s fights with NASCAR and specifically Bill France Sr., goes back almost as far as the birth of the sanctioning body.

In 1950, Flock ran all the events in NASCAR’s modified division, and was declared series champion for that year. Following the end of the season, Flock agreed to run in an event for young promoter Bruton Smith at a new track near Charlotte. France told Flock he was not allowed to run the race due to it being an “outlaw” track (i.e., a track not sanctioned by NASCAR). France further said that if Tim ran the event, he would be stripped of all NASCAR points, despite the season being over.

Flock, never being one who liked to be told what to do, ran the race. France stripped Flock of the 1950 modified title, something that angered the Tim the rest of his life.

At Daytona Beach in 1952, Flock streaked across the finish line 18 seconds ahead of Atlanta’s Jack Smith in the February modified division race. Smith, however, was flagged as the winner. Flock called for a scoring check, which showed that he had indeed won the race. Smith was placed in second.

Smith, however, had other ideas.

When Flock showed up at the beach, his car did not have roll bars. The rulebook for 1952 stated that roof supports would be mandatory for all events. Flock discussed the situation with Bill France, and France ordered some of his track workers use two-by-fours to construct a roll bar out of wood.

After the race, Smith went to the NASCAR officials to protest the wooden roll bars. The officials took the win away and gave it to Smith, despite France himself having given not only the okay for the wooden roll bars, but having had his own track workers help in constructing them. Flock was relegated last place.

Despite the disappointment, Tim would put together a great 1952 season in the Grand National division, piloting his Hudson Hornet to the championship title over Herb Thomas.

Two years later, in the Feb. 21, 1954 Grand National event, Flock drove an Oldsmobile owned by Kentucky Colonel Ernest Woods. Three laps in, Flock took command of the race.

Flock dominated most of the event while being in constant communication with the pits via a two-way radio, the first time such was used in a Grand National event. Flock took the checkered flag by almost a minute and a half.

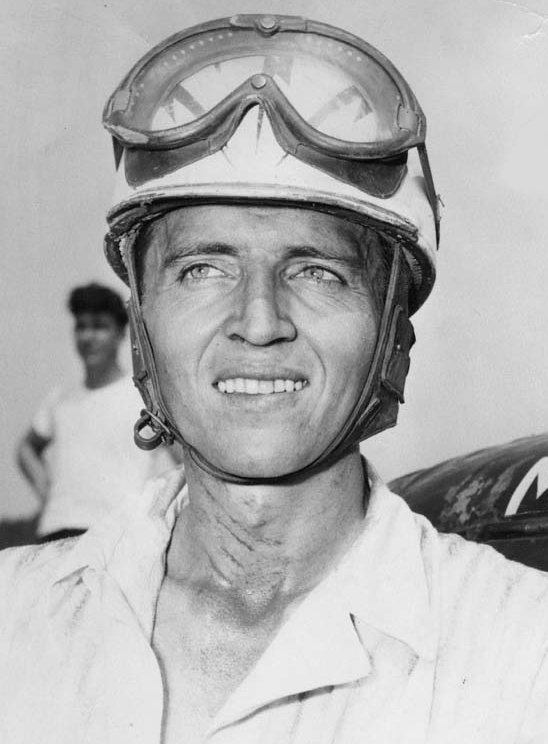

Tim Flock is congratulated in victory lane after the 1954 Grand National event on the beach. Flock would later have the win stripped from him hours later. Photo courtesy Frances Flock.

But in post race inspection, officials found the butterfly shaft on Flock’s carburetor had been soldered to keep it from vibrating loose. Flock was disqualified, and the win was given to Lee Petty.

Tim argued that the soldering gave him no advantage and only prevented potential problems. The race officials did not agree. Flock swore he was through with NASCAR, and sat out most of the 1954 season.

After a year’s absence, Flock returned in 1955 and had one of the greatest seasons ever by a driver, winning 18 races and his second Grand National title.

But perhaps the greatest incident came in 1961, when Flock and fellow driver Curtis Turner attempted to help unionize the drivers on NASCAR’s premier circuit.

France was incensed that anybody would try to unionize his drivers. He threatened to close down his tracks and lock the drivers out of racing, causing Flock and Turner to lose the support of their fellow competitors. France then proceeded to ban both men from NASCAR for life.

Both were eventually readmitted, but not until after Flock had retired from driving.

In a 1993 article in American Racing Classics magazine, Tim said he felt it all came about because France, Sr. was mad at Tim and his brothers Fonty and Bob.

“Us three brothers brought crowds for years to help him along,” Flock said. “They have named all the grandstands, all the big stuff, and gave it to other drivers. Bob, Fonty and me were a big pull. We were most loyal to NASCAR as well. We tried to help him build NASCAR and we did. But they forgot about it. Billy Jr. (Bill France, Jr.) just speaks to me. That’s all. Then he walks on by.”

If Flock sounded bitter, he had reason to. He raced back when failing post-race tech didn’t just mean a slap on the wrist. It could cost you a title, and a whole year’s worth of work.

That makes a $25,000 fine seem mighty small, doesn’t it?

Brandon Reed is the editor and publisher of Georgia Racing History.com.

Questions, comments, suggestions? Email us!

This website is not affiliated with or endorsed by the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame or the Georgia Auto Racing Hall of Fame Association, Inc. All content is the intellectual property of the individual authors. All opinions are those of the individual authors. Please do not repost images or text without permission.