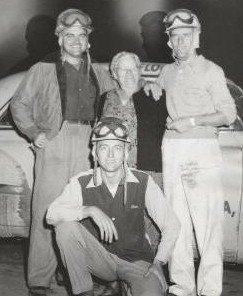

Brandon Reed, Kyle Petty and Robert Marlow smile for the camera in late 2000. Photo from the Brandon Reed collection

By Brandon Reed

Posted in Columns 5/23/11

Since launching Georgia Racing History.com almost two years ago, the one question that I’ve been asked over and over again is “How did you ever get so interested in racing and in its history?”

That answer is very simple. If not for my grandfather, Robert N. Marlow, this website and my connection with auto racing likely would never have come to be.

If there was a race on television, we watched it together. Back before all the races were televised, we would listen together to the races on the radio. We attended events at Georgia International Speedway (now Gresham Motorsports Park) just up the street from us, and at Lanier Raceway in nearby Braselton, Georgia, with an occasional trip to Woodstock, Georgia to the famed Dixie Speedway to see dirt track action.

We would talk about racing. While we watched guys like Bill Elliott, Darrell Waltrip and Harry Gant slug it out, Poppa would tell me about heroes like the Flock brothers, Curtis Turner, and Lee and Richard Petty. He would often tell me what he felt made these men the best of the best, and his love of the history of the sport transferred to me early on.

Poppa’s love for racing came naturally. A self-taught mechanic, he served in the army as a sergeant in the motor pool. After his service to his country ended, he came home, determined to be a top mechanic.

But things didn’t move as quickly as he had hoped, as he looked for work in shop after shop in the Atlanta area. As he worked to establish himself as a mechanic, he supplemented his income by selling coffee door to door.

It was doing this that he became friends with the Flock family. He sold coffee to brothers Tim, Fonty, Bob and Carl, who lived near each other in the Atlanta area, along with their mother, Maudie, who was better known in racing circles as “Big Mama”.

Every time Poppa, who was 6’7” tall and skinny as a rail, visited Big Mama, she would say “How in the world can a man as skinny as you work so hard?” She would then insist he sit down for breakfast with her. He treasured his memories of his friendship with the Flock family, and was able to rekindle that briefly when he was reunited with Tim shortly before Tim’s passing in 1998.

By the late 1950s, Poppa was well established as a top mechanic in and around the Atlanta area. At the same time, his love for speed and the competition of racing was growing. He set his next goal as being part of a winning racing effort, either turning the wrenches or behind the wheel.

He became friends with some of the local racers and mechanics and, when fellow Atlanta engine tuner Paul McDuffie was named to head up Chevrolet’s return to NASCAR in 1960, he snuck into a private test at Atlanta’s Lakewood Speedway to introduce himself.

Poppa never met a stranger, and soon became friends with McDuffie and with driver Joe Lee Johnson. He would volunteer his own time after work at McDuffie’s shop, helping to prepare the race cars. He would quietly be a behind the scenes part of the team’s first win in the inaugural World 600 at Charlotte.

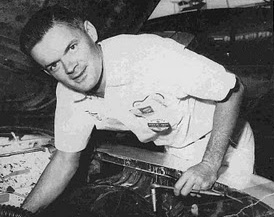

Georgia Racing Hall of Fame member Paul McDuffie.

Poppa strove to become a full time mechanic on McDuffie’s crew, and had even convinced Paul to give him a shot behind the wheel in a test session set for later in the year.

It looked like everything would come together for Poppa when McDuffie asked him to be on the pit crew for his number 89 entry in the Southern 500 at Darlington. Elated, Poppa went home to pack for the trip.

My grandmother, however, had other ideas. Racing back then was not the sort of thing that was thought highly of, and she had no intention of her family being a part of it. She told Poppa that if he wanted to go to Darlington, that was fine. When he got back, however, she and their young daughter, Elaine, would be gone.

Poppa unpacked his bag and didn’t make the trip. During the running of the Southern 500, McDuffie and two others were killed when Bobby Johns’ out of control car slammed into the pits.

After the incident, Poppa gave up on the idea of being a racer or a racing mechanic. He would instead strive to be a preacher, starting a ministry that reached out to inmates at North Georgia prisons. But his love for racing and his admiration for those that raced remained. He would continue to follow the sport as an avid fan.

So it should come as no surprise that Poppa’s love for the sport would carry over to his first grandson. Some say the love for cars and racing starts at birth. In my case, it was truly inherited.

Robert Marlow in 1966. Photo from the Brandon Reed collection

There are so many stories I could tell you about racing with Poppa. Like the first race I ever attended with him at Georgia International Speedway. His explanations of how the cars worked, how he would point out different things over the course of a race.

Or how, when I was in high school, he would help me rig up a pocket size radio with a single ear plug fed up the sleeve of my jacket to I could quietly listen to the Twin 125 qualifiers at Daytona in February. Or how he looked the other way when I skipped school in 1992 so I could listen to Richard Petty’s final Daytona qualifying appearance.

But maybe the best ones I could tell you are the two I tell most.

In 1998, NASCAR celebrated their 50th anniversary. With that in mind, the annual Winston Preview in Winston-Salem, NC was slated to have a distinctively historic flair. Poppa and I decided to take the trip for the event in January, and to also make a trip to Petty Enterprises in Level Cross, NC to see the Petty compound.

All the way up, Poppa talked about wanting to meet family patriarch Lee Petty. I explained that Lee generally didn’t come out and talk to people. He usually just kept to himself. But Poppa insisted that he would meet Lee, no matter what.

Robert Marlow holds court at Richard Petty's museum in Level Cross, North Carolina, in 1998. Photo by Brandon Reed

When we arrived later that morning in Level Cross, we visited the Petty Museum, which at that time was adjacent to the Petty shop. We spent much of the day there, touring the museum and, on Poppa’s part, spending a lot of time talking to Doris Gammons and the other ladies who worked there.

At one point, Poppa excused himself to step outside for a cigarette. After a few minutes, it dawned on me that Poppa was on his own, unaccompanied in Level Cross with the sole goal of talking to Lee Petty.

Just as I got outside, I found Poppa down on his knees, his head stuck under the fence that separated Lee’s house from the rest of the Petty compound, yelling “Lee! Lee Petty! Come on over here!”

I looked up to see Lee Petty, golf club in hand, ambling over towards us. Poppa would later tell me that, while standing there smoking, he saw a golf ball go rolling past on the lawn, and realized that Lee was out there practicing.

As Lee walked towards us, Poppa, who as I previously said never met a stranger, pulled himself up to his full 6’7”, stuck out that big hand of his and said, “Lee Petty, my name is Robert Marlow.”

Lee took his hand and shook it, saying “Robert Marlow, my name is Lee Petty, and I’m glad to meet you.”

Poppa looked Lee right in the eye and said “Lee Petty, I’ve been waiting almost 40 years to tell you this. I hate your guts!”

Instead of being indignant, Lee started laughing.

Poppa continued, “I hated you when you won all them races in them damned old Plymouths and them damned old Olds-a-mobiles, because I’m a Ford man.”

“But you loved me when I won Daytona, didn’t you?” Lee asked, still laughing.

“No I didn’t, because you won it in a damned old Olds-a-mobile, and I just told you I’m a Ford man,” Poppa said. “But in 1964, I went to work for Downtown Dodge in Atlanta, Georgia, and every time that you and Richard and Maurice won, you made me more and more money. And that’s why I love you, Lee Petty!”

We were told later that if he had approached Lee any other way, he probably would have cussed and walked off. But Poppa never met somebody that he didn’t win over as a friend.

The second story is dependent on the first, as it again dealt with the Petty family.

In April of that same year, 1998, fourth generation racer Adam Petty made his professional debut in an American Speed Association event at our hometown track of Georgia International Speedway (then Peach State Speedway, now known as Gresham Motorsports Park) in Jefferson, Georgia.

Poppa called me and asked if I wanted to go with him to qualifying the day before the race. I said sure, and met him there. We were good friends with the track promoter, the late Rob Joyce, who told us we were welcome just to go on down into the pits and see everybody once things were done.

We did just that. Poppa’s lone goal on that day was to meet Adam Petty. He had been following the young driver’s short track exploits closely, and felt he was a racing superstar in the making.

We indeed met Adam, who called his father Kyle Petty over to meet us as well. We shared with them the story of Lee Petty and the “Ford Man”. They laughed and laughed at the story.

Kyle said “You guys have got to come back for the race tomorrow night, please. Promise me you will both come out here tomorrow for the race.”

How could we refuse?

So the next day, there we were, front and center at Adam’s first race. We went down on the front stretch prior to the race for the scheduled autograph session on the starting grid and, of course, headed straight for Adam’s car.

He thanked us for coming back, and said “Hey, would you guys please hang out over here next to me for a little bit?” We did so, and Poppa commented on Adam’s interaction with the fans by simply looking at me and saying “He’s just like his granddaddy.”

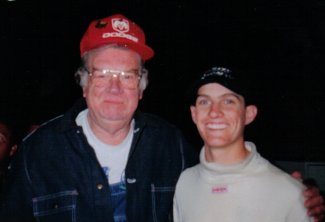

Getting Adam's autograph. Photo by Brandon Reed

About that time, Poppa got a tap on the shoulder. It turned out to be from a member of Adam’s crew, who asked Poppa if he could make it to the other side of the pit wall.

“I can, sir,” Poppa said, “But why do you want me to?”

“Mr. Petty sent me,” he said. “He’d like for ya’ll to come over to the pits and hang out with him and the King before the race starts.”

Poppa took a quick look at me, then put both hands on the top of the pit wall and climbed all 6 feet and 7 inches of his then 68 year old frame over the wall.

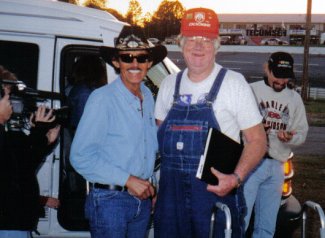

When we got back there, we were warmly greeted by Kyle. After talking for a moment, I looked over to see Richard Petty walk over to Poppa, with his hand extended.

“This must be the famous Ford Man I’ve been hearing so much about,” Richard said, flashing that Petty grin. “I used to be a Ford man myself. I backed one into the wall over there in turn two here back in 1969.”

Richard pointed out that Poppa was wearing a Dodge cap. Poppa said he had worn it that night to “be diplomatic”.

The King and The Ford Man meet at Gresham Motorsports Park in 1998. Photo from the Brandon Reed collection

Here were the two biggest heroes in my life, Robert Marlow and Richard Petty. It was a memorable moment.

But it wasn’t over yet.

Richard said to Poppa, “Sir, are you from around here?”

The track was built in the same field that Poppa had picked cotton in as a young man.

Poppa said, “Richard, I’ve peed on every rock in this field.”

I thought Richard was going to fall down he was laughing so hard.

Incidentally, Poppa took the news of Adam’s tragic passing in 2000 very hard. Late in the year, when Kyle Petty made a personal appearance at a Pontiac dealership outside of Atlanta, he insisted we go.

After everyone had an opportunity to get an autograph, Poppa approached Kyle (who had remembered us right off). He put his arms around Kyle’s shoulders, and leaned in close, talking softly to Kyle so nobody else could hear. I never asked what he told Kyle, but his words seemed to mean a lot to him. He hugged Poppa, thanking him.

There are so many more stories I could tell you, so many more things I could share. But it would never seem like enough.

My own father, to be blunt, was useless. He was a liar, a thief and a flim flam man. I’ve not laid eyes on him in almost 25 years.

Poppa stepped into that role, being my grandfather, father figure, racing buddy and dear, dear friend. He was one of the most important people in my life.

Over the last few years, he had been in declining health. On the morning of May 19, 2011, he passed away quietly in his sleep.

He was a great man who made many friends, helped many people and was loved by his family.

He was also the best grandfather that anybody could have ever hoped for.

I love you, Poppa. And I know damned well you can hear me. I love you, and I miss you.

Brandon Reed is the editor and publisher of Georgia Racing History.com.

Questions, comments, suggestions? Email us!

This website is not affiliated with or endorsed by the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame or the Georgia Auto Racing Hall of Fame Association, Inc. All content is the intellectual property of the individual authors. All opinions are those of the individual authors. Please do not repost images or text without permission.