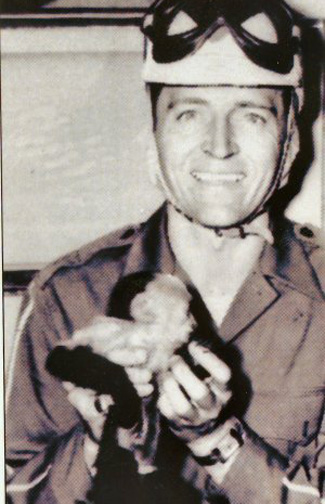

Tim Flock and his 1953 co-driver, Jocko Flocko. Photo courtesy Frances Flock

By Brandon Reed

Posted in Feature Stories 7/16/10

When the American automobile racing scene was in its infancy, having a passenger in a racing car was a common thing to see, as drivers would have “ride along” mechanics to help them during races.

These mechanics would diagnose any problems with the car, as well as to warn the driver when someone was approaching them from behind or preparing to make a pass.

The first warning sign that the days for the ride along mechanics were numbered came when Ray Harroun won the inaugural Indianapolis 500 in 1911. In that event, Harroun gained an edge by using the first rearview mirror, making his racing machine lighter and eliminating the need for a mechanic as a passenger.

Although the riding mechanic would stay around in certain forms of racing for several more years, by the time stock car racing began to make its big splash, race drivers really didn’t have a need for passengers.

However, in 1953, NASCAR did see its only co-driver in eight Grand National (now Sprint Cup) events.

His name was Jocko Flocko, and he was a Rhesus monkey that rode shotgun with Georgia Racing Hall of Fame driver Tim Flock.

It’s the kind of story that’s so crazy, there’s no way that it could be made up.

Tim Flock saw much success in 1952 driving Hudson Hornets for Ted Chester, pictured right. Both are now members in the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame.

Back in 1952, Tim Flock recorded the best season of his career driving for Dawsonville, Georgia native Ted Chester. Piloting Hudson Hornets wrenched by famed Atlanta mechanic B.B. Blackburn, Flock recorded eight wins, and bested Herb Thomas for the Grand National championship title.

In 1953, Flock was back behind the wheel of Chester’s Hudson, and looking for more trophies for his shelf.

As the story goes, Chester was in Atlanta during the early part of 1953. He was visiting a pet shop to purchase a gift for a family member when he spotted a small Rhesus monkey in a cage. The cage had a sign on it saying that the monkey’s name was “Jocko.”

Chester’s mind instantly clicked in on the name “Jocko Flocko,” in association with Tim. What a marketing gimmick for his race team to have a cute little monkey ride shotgun with Tim during the races!

Chester purchased Jocko and took the idea to Flock.

Tim told the story this way in Larry Fielden’s book, “Tim Flock, Race Driver”:

“I thought Ted had been hittin’ the jug too much. He couldn’t be serious. But the more I got to thinking about it, the more I liked it. Jocko Flocko could race with me anytime – if he proved he could handle the Grand National Circuit.”

Chester and Flock didn’t know how the NASCAR officials would respond to the idea of having a monkey in the race, so they just didn’t bother to tell anybody.

Chester had a driving suit made up for Jocko, complete with his name and the car number on the back, along with a helmet. Safety, of course, was a priority.

Chester also had Blackburn design and install a special seat for Jocko on the passenger’s side that was high enough so that Jocko could see out the window. That would allow him to wave to the fans or to the cars that he and Tim passed during the race.

Tim and Jocko's first race was at Charlotte. Here, Tim (91) looks for a way around Buck Baker (87) in the early laps.

Jocko’s first race was a 150 lapper at the dirt track in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Just before the race, Tim’s crew smuggled Jocko into the car, and buckled him into his little seat.

Tim would lead seven times for 87 laps, lost power with 24 laps to go, handing the win to Dick Passwater. Flock would hang on to finish fourth, collecting $350 in winnings. It’s not noted how much Jocko got for his services.

After the race, Tim took Jocko over the grandstands. Word had gotten out that he had the little monkey racing with him, and he was an instant hit. The fans clamored to meet, pet and feed Jocko peanuts. He was an instant fan favorite.

Jocko would go on to race in eight events with Tim. They would finish sixth in their next event at Macon, Georgia, recorded a fifth at Langhorne, Pennsylvania, and a second at Columbia, South Carolina.

The biggest moment in Jocko’s racing career came on May 16, 1953, when he and Tim finally broke into Victory Lane as teammates in a 200-lap event at Hickory, North Carolina. The team pocketed $1,000 for the win. Jocko’s cut was in peanuts.

NASCAR, meanwhile, simply turned a blind eye to the high-speed simian. They recognized a golden opportunity to bring much needed publicity to the still young Grand National tour. The attention that Jocko Flocko got as Tim’s co-driver equated to more tickets sold for each event.

A rare look at Jocko Flocko in his uniform prior to a race.

Jocko’s presence also helped out on the competition side. Years later, Tim would say that when Jocko was riding with him, the two would dive to the inside of a competitor. The opposing driver would look over to see who was there, and see Jocko staring back at him. The surprise would break the driver’s concentration for just a second, but that’s all Tim needed to pass him for the position.

The Flock-Flocko pairing hit a rough patch over the next couple of races. Hopes were high when they went to Martinsville, Virginia on May 17. The team’s Hudson broke a spring 18 laps in, relegating them to a 32nd place finish.

Things didn’t get much better when the team traveled to Columbus, Ohio for an event on May 24.

Prior to the event, Tim and his brother, 1952 Southern 500 winner Fonty Flock, checked into a motel near the half-mile Powell Motor Speedway, along with Jocko. The brothers left Jocko on his own in the motel room while they went out to check in at the track and unload their race cars.

While they were gone, Jocko managed to get out of his cage and was playing around in the room. Shortly thereafter, a maid came by to bring some towels to the room. Seeing the woman, the playful simian saw an opportunity to have some fun.

Jumping out of hiding, Jocko landed on the maid’s back and started pulling her hair. Jocko, who wouldn’t harm a fly, was simply playing, and having fun.

The maid, however, thought some unholy creature had a hold of her. She exited the room screaming, arms flailing through the air.

The Flock brothers and Jocko were booted out of the motel, and they had to spend the night in their cars.

Things didn’t go much better for Tim and Jocko the next day, as a bad bearing left them with a 22nd place finish.

Jocko and Tim were looking to turn things around, and paved, one-mile long track in Raleigh, North Carolina looked to be just the place to do it in.

Instead, it would prove to be the final race in Jocko Flocko’s short career.

Fonty Flock took top honors in the Raleigh 300. From left to right is mechanic Red Vogt, Fonty, and car owner Frank Christian. Photo courtesy Frances Flock

Forty-Nine cars took the green flag for the Raleigh 300 on May 30. Late in the race, Tim found himself running second to brother Fonty as the laps wound down.

Back in those days, Grand National cars raced on regular street tires. There was no such thing as a specially designed racing tire in NASCAR at that time.

To monitor tire wear during the race, teams would cut a small trap door into the wheel well on the right front tire, and attach the door to a small chain. The driver would periodically pull the chain, opening the door, and they could see how the tire was wearing. If they began to see the white of the tire cord, they knew they would have to pit soon.

During the course of the previous seven races, Jocko had watched Tim open that little door a thousand times. He was a curious little fellow, and wanted to see what all the fuss was about.

As the race wound down, Tim was focused on trying to catch Fonty. Jocko, meanwhile, managed to slip out from under his seat belt, and climbed down into the floorboard to have a look at the trop door.

As Jocko pulled the chain and opened the door, the tire apparently kicked up a small piece of gravel, which barely zinged the little monkey between the eyes.

Jocko let out a scream, and began running around the inside of the Hudson. He eventually ended up on Tim’s back, clawing and screaming at the top of his lungs.

All this at 100 mph around a one-mile race track, in competition.

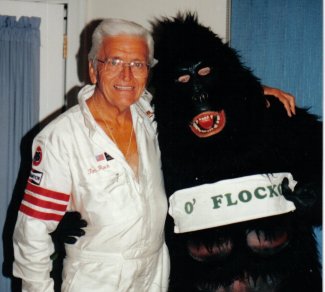

Tim shares a moment with one of Jocko's relatives during the 1991 Winston Legends weekend at Charlotte. Photo courtesy Frances Flock

Tim showed put on an incredible show of car control, and piloted the Hornet into the pits (I dare anybody to argue my “car control” assertion. When’s the last time you saw Kyle Busch drive a car with a screaming monkey on his back?). Once stopped, he handed the frightened monkey out to a crew member before returning to the race.

In the meantime, Speedy Thompson slipped by on the track, relegating Tim to third. That’s where he would finish, behind Fonty and Thompson. The impromptu pit stop cost him $600 in prize money.

Needless to say, Jocko was fired on the spot. He retired to the relative quiet of the Flock household, where he happily lived out the rest of his days.

In their time together as a team, Tim and Jocko would pocket $3,945, making Jocko Flocko the most successful simian in NASCAR history.

Over the years, fans would come up to Tim and ask, “Whatever happened to Jocko Flocko?”

Tim would flash that trademark mischievous Flock grin, and say, “I couldn’t teach him to sign his autograph, so I had to fire him!”

Brandon Reed is the editor and webmaster for Georgia Racing History.com.

Questions, comments, suggestions? Email us!

This website is not affiliated with or endorsed by the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame or the Georgia Auto Racing Hall of Fame Association, Inc. All content is the intellectual property of the individual authors. All opinions are those of the individual authors. Please do not repost images or text without permission.