Second Race – July 25, 1948

Red Byron poses for a photo the day of the July 25, 1948 NASCAR race at Columbus. Byron was in contention for the win when tragedy struck. Photo from the R.T. Milford collection

The next race at Columbus was held a month later on July 25. Unlike the previous month’s event, the race was a bonafide NASCAR points event.

Many of the best drivers would be there, including Atlanta’s Gober Sosebee, who had won the previous week at Macon. Also Jack Smith, who had set a new track record at North Wilkesboro seven days prior, and Roscoe Thompson, the up and coming Atlanta driving star who began his career in the Soap Box Derby series.

France’s infant circuit was barely seven months old when their staff arrived that week. That same day, July 25, NASCAR was holding a double feature, formulated at the time as a necessity for distance and travel as a comp for the competitors. This race was held at the Greensboro, North Carolina Fairgrounds track.

Red Byron and Fonty Flock were in a heated battle for the points lead of NASCAR’s stock car championship. A win by Byron would put the battle in a near dead heat at the season’s halfway point. Today the two Georgia stars would be in Columbus.

France was at the Greensboro track. He said from there he needed to go to nearby Lakeview Speedway in Lexington to advertise his next points event. His rival promoter, Sam Nunis, had mailed out over 250 entry blanks in a shotgun effort to lure some of NASCAR’s best to the NSCRA event in Chattanooga, since so many of the boys were racing south of there.

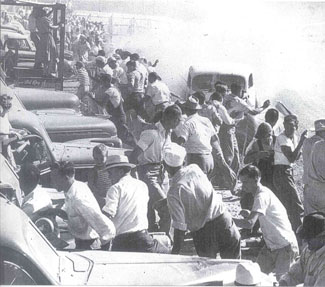

The view from turn one, on the Blackmon Road side of the track, shows just how close and unsafe fans could get.

Former driver “Lucky” Sauers of Rosman, North Carolina was sent down to be France’s official starter at Columbus, as regular flagman Alvin Hawkins worked the Carolina event.

For the first 38 laps of the 40-lap feature, everything seemed to fall right into place. There was a packed house, and a cream-of-the-crop field. Points leader Fonty Flock was driving a new car built just for this Columbus race. Jack Smith had set a track record in qualifying, besting Bob Flock’s time from the previous month’s opener.

To that date, no fatalities had occurred in any NASCAR event. But on that day, tragedy would strike twice. Everything went terribly wrong at both tracks.

This is what driver Stan Parnell said at the time from Columbus:

Charles Jenkins was near the fence and witnessed Red Byron's wreck.

“Billy Carden was attempting a late charge to catch the leader, Red Byron. Carden’s move to pass was blocked by Byron as he dropped down in turn three. Red’s right front tire blew. From then on, his was simply out of control.”

Charles Jenkins, a Columbus native whose father used to jump cars in the early days driving a 1921 Willis-Overland (Jeep) at the local fairgrounds, was within feet of the accident.

“We were watching from the middle of the third and fourth turns,” Jenkins said. “My wife and her friend walked to the fence. After the first heat, I felt uneasy and got them to back away and stand in the bed of a friend’s pickup truck.”

Two laps from the finish, all hell broke loose.

“I remember it very clearly,” Jenkins said. “As Red came flying into the turn, you could hear the engine breathe briefly. At that moment I recall his right front tire exploding, the one where in the curves most of the car’s weight is pressed. I watched him try everything he could to spin the car and avoid the crowd gathered at the fence. Apparently his one final gasp of hope was to gas it, pulling left at the wheel, apparently hoping to power spin it in harms way of the other racers – anything other than ramming into a pack of spectators.

Red Byron's car plows into the fence during the event, injuring several spectators and leaving a seven year old boy dead. Photo courtesy Eddie Samples

“Regardless, the car kept nudging that bank, and finally climbed it and hit.”

“I never remember the car going all the way through the fence,” he continued. “The people were pressed so close his car just raked along doing damage. I remember a huge wooden post flexed enough from the impact, it ‘head-popped’ the little boy that later died at the hospital. The child’s father picked him up and put him in the family car and left. He did not wait on the ambulance. People were lying around everywhere. A friend of mine had his ankle broken.”

All together there were 17 unfortunate spectators when Byron’s 1939 “Raymond Parks Novelty Company” black and white Ford coupe lapped and poked its way along the cattle fence “retaining wall”.

Veteran South Carolina driver Charlie Rush, who had just slung his Dodge into the third turn, had a harrowing view of the moment.

“Those huge wooden posts were deep in the ground, with about five feet above earth,” he said. “They were strong enough to slightly straighten Byron’s car and kept him from plowing directly through the crowd. It was a very unsafe situation, but we just didn’t know back then because it had never happened.”

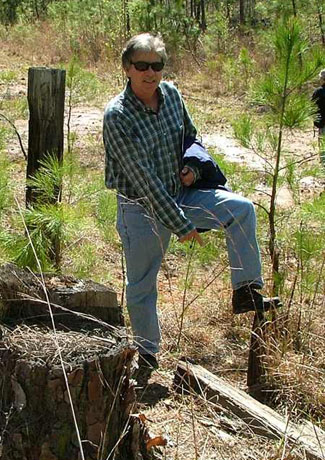

View of posts still at the site after nearly 60 years. Facing turn three, spectators on the left, track to the right.

When all was done, seven-year-old Roy Brannon was dead. The rest of the injured list ranged from an amputated leg to a fractured pelvis, and several with broken legs and ribs.

GARHOFA's Don Ray marks the actual spot of the accident.

Track manager Hill noted the next day, “the accident was strictly unavoidable. Byron’s car was unmanageable rather than out of control at the time of the wreck. I would attribute the accident to mechanical failure.”

Mableton, Georgia’s Billy Carden was given the red and checkered flags immediately after the accident.

“It was a sad sight,” Jenkins said. “Red just seemed helpless after the wreck. He walked back around to the flag stand. I felt sorry for him. That was the first time I knew that he had a bad leg (Byron’s left leg was injured during the war). I could see his foot was flopping. You could tell it was an old injury. He wasn’t putting on or anything because of the wreck.”

As with the first race at Columbus on June 20, it was in the record book again. But this time it was a sobering event as the newly formed NASCAR, only five months old, has their first fatalities. Ironically, and tragically, on the same day at the Greensboro event, driver Bill “Slick” Davis of Concord, North Carolina was killed. His 1937 Chevrolet turned over several times and he fell out of the car onto the track in front of oncoming traffic. He died later that night.

So within a few short hours, NASCAR recorded their first fatalities for both spectators and drivers. Police later listed Davis’ death as an “occupational accident”.