Harold Kite won at Daytona Beach in 1950, but his racing legacy continues on today. Photo courtesy GRHOF

By Brandon Reed

Posted in Feature 8/13/11

A racing legacy can take several different forms. Sometimes it comes in the form of a racing dynasty spanning many years with a number of wins and championships.

But another kind of racing legacy can come from the impact that someone had on the racing world in a relative short period of time, and how that impact continues to resonate today.

Such is the racing legacy of Harold Kite of East Point, Georgia.

Kite was born on November 13, 1921. Like many others before him, Kite’s love for all things automotive came from being born into a portion of the business. His family was in the auto parts business, so being involved with cars was automatic.

Kite served in World War II as a tank driver. That training would serve him well for his exploits following his service.

After coming home from the war, Kite, like many of his fellow servicemen, found excitement in competing at his area race tracks.

Kite began competing and winning in stock cars at the famed Peach Bowl Speedway in Atlanta and at the legendary Lakewood Speedway just south of downtown Atlanta. He would travel to Birmingham to compete at the fairgrounds and at the Iron Bowl in Alabama, picking up wins here and there along the way.

He even competed in a midget racer for Georgia Racing Hall of Fame member Jimmy Baker at the Peach Bowl.

At the same time, his fellow Georgia drivers were traveling south to Daytona Beach, Florida and finding great success on the beach and road course there. It would become the epicenter for a new stock car sanctioning body called NASCAR, headed by Bill France, Sr. beginning in 1948.

Twice, Kite made the trip to the Sunshine State to compete in NASCAR’s modified division on the beach, in August of 1948 and in January of 1949.

1949 marked the first year for France’s much touted Strictly Stock division, which would later become today’s Sprint Cup Series. While he stuck to modifieds in 1949, Kite decided that he might give the new division a try with the 1950 season opener. He warmed up for those events by competing in two non-NASCAR strictly stock events promoted by Sam Nunis at Atlanta’s Lakewood Speedway late in ’49.

That opener would be the first February event to be held on the beach, and the decision would prove to be a good one for Kite.

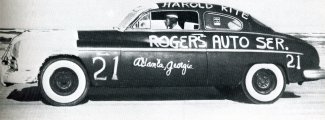

Harold Kite in the #21 1949 Lincoln he piloted at Daytona Beach in 1950. Note that the front end has been heavily taped up to protect the paint so the car would retain its resale value. Photo courtesy GRHOF

Kite would carry a 1949 Lincoln sponsored by Roger’s Auto Service to Daytona for the event. Maybe it was his training as a tank driver over tough terrain that gave him an edge, as he quickly took to the rough and rutted beach course, timing in third fastest in time trials behind Joe Littlejohn and J.C. Van Landingham.

The field would actually start five wide for that race, with Bill Blair and Tim Flock sharing the front row. On the drop of the green flag, Littlejohn faltered slightly, giving Landingham and Flock the advantage.

But Kite muscled his way past his competitors and took control of the event, leading the first lap. He would continue to set the pace as several of his competitors encountered early trouble. Littlejohn and Blair suffered mechanical failures seven laps in. Frank Mundy’s Cadillac was sidelined. Hometown heroes Fireball Roberts and Gober Sosebee were out by lap 21.

As Kite worked over lap traffic, Red Byron, 1949 champion and perennial favorite on the beach, had pushed his Raymond Parks owned Oldsmobile though the field and, by lap 21, trailed only Kite in the rundown. Keep in mind that, just six laps in, Byron had found the brakes in his Olds gone, and was using the emergency brake to make the turns. Despite this, he was consistently faster than his competitors.

On lap 12, Kite made a miscalculation, overshooting the south turn and almost becoming bogged down in the sand. That gave Byron the opening he needed, as he charged past Kite’s Lincoln and into the lead.

Kite recovered and gave chase. His Lincoln had the advantage on the straighaways over Byron’s Olds, but Byron could negotiate the turns better, even with the lack of a proper braking system.

But on the 24th lap, Byron was coming back up through the gears after negotiating a turn only go have the car hang in second gear. He managed to get to the pits, where master mechanic Red Vogt made some hasty repairs. The stop handed the lead back to Kite, and left Byron some six miles behind the leader in seventh place.

Kite would hold the lead the rest of the way, but Byron still made it interesting. He would pass Kite once to get back on the lead lap, and would make his way back through the field to second, closing to about a minute behind the leader.

But there was no catching Harold Kite, who recorded the win in his first NASCAR Strictly Stock outing, picking up a cool $1,500 for the win.

The trophy for the win rests in a place of honor today at the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame in Dawsonville, Georgia.

Kite would compete twice more in the Strictly Stock series in 1950, finishing 38th at Darlington and 12th at North Wilkesboro.

In 1951, Kite would turn in a sixth place effort in the Southern 500 at Darlington, driving an Oldsmobile for Julien Buesink. He would pilot the same car to a 29th place finish at Columbia, South Carolina that same year.

After a three year absence from NASCAR’s top series, Kite would return in 1955 to finish 25th at Memphis-Arkansas Speedway, and 43rd in the Southern 500.

Kite would make his last appearance in a Grand National car for some time at the Cleveland County Fairgrounds in Shelby, NC, where he piloted a Ford to an 11th place finish.

At the same time, he continued to compete at the Peach Bowl, Lakewood and other small tracks around the south, picking up wins and competing against other Hall of Fame caliber racers.

But after a nine year absence from NASCAR’s top circuit, the lure of the new big, fast superspeedways and the rich paydays that came with them proved to be too much for Kite, who decided to enter the fall Grand National event at Charlotte, North Carolina.

Things started out well enough. Piloting a Plymouth owned by Harold Mays, Kite turned in the 24th fastest time out of 44 starters. As the race started, 14th place starter Junior Spencer had trouble getting his Ford to start. Kite, always the gentleman, pulled up behind Spencer and gave him a push to get the Ford started. With such a sportsmanlike gesture, it was sure to be a great start to the day.

But things went bad in a hurry. On the second lap of the event, as a pack of cars fought for position, Rock Harn, Sonny Hutchins and Frank Warren tangled in the third turn. With the accident unfolding right in front of him and leaving the track blocked, Kite slid his car sideways to avoid the spinning cars.

The remains of Harold Kite's Plymouth are towed away from the accident scene at Charlotte Motor Speedway. Kite would pass away in the track's infield care center.

Jimmy Helms also ducked low to avoid the melee. When Kite’s Plymouth slid down the banking, it skidded right into the path of Helms’ Ford. It was a simple matter of two cars being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Helms, unable to avoid Kite, slammed into the driver’s side door of Kite’s car still under almost a full head of steam.

The impact was huge. Kite suffered massive internal injuries and a severed leg. He would be transported to the infield care center, but had lost so much blood in the course of the accident that he had very little chance of survival. At 43 years of age, Harold Kite passed away as doctors worked to save his life.

Over the years, it would have been easy for Harold Kite’s name and his accomplishments to simply become a footnote in the vast annals of racing history.

But rather than be a footnote, Kite’s life and his career are a true racing legacy. Kite’s daughter, Lisa Carson, has served as a long time volunteer at the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame in Dawsonville, Georgia. Lisa has long taken pride in showing visitors her father’s Daytona Beach winner’s trophy, along with the photos she has loaned to the Hall of Fame for display over the years.

She also makes it a point to tell visitors that any white, puffy clouds that float in the sky above the hall are “my daddy doing a burnout for me in the sky to brighten my day.”

That, along with the fact that he was named as a 2011 inductee into the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame, insures that the racing legacy of Harold Kite will continue to grow and live on for generations to come.

Brandon Reed is the editor and publisher of Georgia Racing History.com.

Questions, comments, suggestions? Email us!

This website is not affiliated with or endorsed by the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame or the Georgia Auto Racing Hall of Fame Association, Inc. All content is the intellectual property of the individual authors. All opinions are those of the individual authors. Please do not repost images or text without permission.