Tommie Irvin

By Brandon Reed

Posted in Feature Stories 12/10/10

On Sunday, December 5, the Georgia racing world lost another dear friend, not to mention a true pioneer in the sport.

2009 Georgia Racing Hall of Fame inductee Tommie Irvin passed away at an Athens, Georgia area hospice in the early morning hours. He had suffered a major stroke on Thanksgiving, and his condition had slowly deteriorated since.

Irvin was born in rural Habersham County, Georgia, where he went to school and played football, basketball and baseball. He joined the army in 1943 at the age of 18, and would serve as a sergeant in Company K 254th Infantry Regiment, 63rd Division. He was awarded several medals, including a bronze star, and was honorably discharged in 1946.

“I was playing football for the University of Georgia, but had more fun hanging out with Swayne Pritchett and Pee Wee Dooley,” Irvin told GRH.com’s Eddie Samples in a 2000 interview. “Pee Wee promoted Habersham County Speedway and owned a garage where we worked on our trip cars. Swayne was driving race cars so it was kind of natural I got started doing the same. It was fun.”

After Dooley lost his life in a gas explosion at his home, Irvin began working out of Jack Edwards’ garage in Cornelia, Georgia. Edwards prepared race cars for Pritchett, and soon he and Irvin would be teamates.

Pritchett raced the number 17 and Irvin piloted the number 18.

Irvin raced locally in the late 40s and early 50s, and was one of the first drivers, along with his friend Swayne Pritchett, to obtain a license from NASCAR shortly after the sanctioning body formed in 1948. Irvin raced all over, including at the famed Daytona Beach road course, where he once ended up running out into the ocean. Irvin was the Southern Racing Enterprises Association champion in 1954, but says his biggest win came at Atlanta’s famed Lakewood Speedway in 1955.

“There must have been sixty or so cars there that day,” Irvin told Samples in 2000. “Lucky for me most of them had only driven on the smaller tracks whereas I had been to Lakewood a few times. I just remember my car was running perfect, and I could pass on the inside or the outside. Anybody could have driven that car.

“There was a wreck on the back stretch and I came in the pits late in the race. Chester Barron owned the car and started complaining I was going to blow the engine if I didn’t slow down, he told me sternly. I told him I wanted to lap the field. It was something I had never done, and just once in my life I wanted to say I did it. He said ‘Well, if you don’t slow down you sure a hell will get your wish.’

“I got my wish,” laughed Irvin. “Like I said, the car was sweet that day.”

Irvin was a constant competitor at Lakewood, where he would square off against some of the best racers of the day.

“You got as fast as you wanted to go,” Irvin said in a 2007 interview. “When you went into that upper turn, you would be running a good bit over 100 miles an hour, which was fast at that time. But when you came down through that lower turn, you’d come out at around 60 or 65 miles an hour. You lost all your momentum going around that lower turn. But coming down that straightaway, you could get on up there. You were really running.”

Along with winning the 1955 Southeastern Fair event, Irvin was present for one of the most legendary moments in the track’s history.

The facility was owned by the city of Atlanta. In an attempt to keep out former moonshine runners, the city fathers passed an ordinance barring drivers who had been convicted of hauling liquor from racing at the speedway.

That led to a day when legendary Georgia racer Bob Flock decided he was going to race, city ordinance be damned.

“I remember it well,” Irvin said in 2007. “I was lined up out there, and this one car kept circling. Nobody realized at first it was Bob, because he had a handkerchief tied over his face. Then a police car came on the track, then another. They got down to the lower end, and had him hemmed up.

“He ran through the fence, and broke some boards. He took off through the field, and went up on the highway, with these police cars chasing him, and they took off down Lakewood Avenue. We found out later that it was Bob, trying to slip in there to race.”

In the same year that Irvin won at Lakewood, he opened Banks County Speedway near Baldwin. Some of the best short track racers of the era would travel to the track to compete, including Bud Lundsford, Tootle Estes, T.C. Hunt and Buck Simmons, all of whom are now members of the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame, along with Irvin. The track would stay in operation until the early 70s.

After the track closed, Irvin continued to follow racing, and would be a life long supporter of the sport he loved so much. In 2009, he was inducted into the Georgia Racing Hall of Fame, and earlier this year was honored as part of the inaugural Georgia Racing Hall of Fame night at Gresham Motorsports Park.

“I love my dogs and I love my racing and all the people I have met by my involvement,” Irvin told Samples in 2000. “I really hated to quit driving more than anything, but I remember my last two races really did me in. One was at Hartwell Speedway and Russell Nelson did a squeeze play on me and forced me into the infield. And at Anderson’s East Park track, I was using that new fuel nitro propane. The stuff made me so dizzy I had to crawl on all fours out of my car. Too old for that anymore. I still have people wanting me to sponsor their cars. I tell them I’m sorry, but it wouldn’t be fair to the rest of my friends who still race.”

For all of his friends and all his admirers, there will never be another Tommie Irvin.

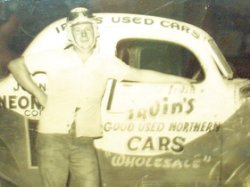

Please continue on for photos from Tommie Irvin’s life and career.